The first thing you should know is that I am so not the stereotypical tech-head who revels in analysing long lines of code.

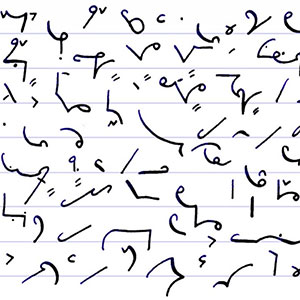

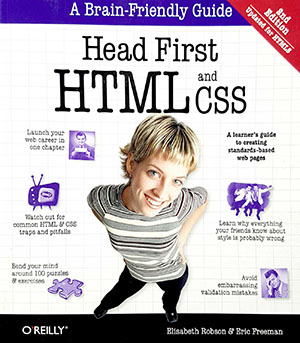

My ability to use HTML and CSS – two of the three main languages used to create websites – happened by accident. I was working at a bookshop in Sydney when a colleague showed me his copy of Head First HTML and CSS: A Learner’s Guide to Creating Standards-Based Web Pages by Elisabeth Robson. This book was so different from other books about computers and web technology that I'd seen. It incorporated many different principles of learning – such as overlearning and using colourful and wacky images and diagrams to ensure that the ideas taught in the book stayed firmly in the reader’s mind.

The text and images are surrounded by a lot of white space – which increases the size of the book – but the payoff is that the content has a spacious vibe and it never feels crammed in. I don’t mind having to deal with a hefty book if it means that I’m going to understand the content, which is not something you can say about most web technology books, which usually fail to keep the reader’s needs uppermost in their priorities. They are, as a result, usually poorly written and largely incomprehensible to the novice.

I bought my own copy of Head First HTML and CSS and since then I’ve been fascinated by the process of creating a website from scratch. I can now understand more complex books on the subject; my next task is to teach myself Javascript, if I can find the time.

I can't begin to tell you how much I love this book. I’d always wanted to create a website for myself from scratch, largely because I can’t stand the cookie-cutter look of websites based on WordPress, Wix and similar sites. Regardless of how many options they offer, they all look so boringly generic, as if they were created from a template – which they were. I wanted to have as much control as possible over the look of my site, and although I’ve had many frustrating moments while trying to get everything working – as does every website creator – it was worth it. Head First was the first book I saw that made me think that a regular person – who didn’t guzzle six-packs of Red Bull or sport an ironic hipster moustache – might be able to learn this stuff. This is true of many of the titles in the Head First series of web technology books.

One more thing: no, I’m not getting sponsorship or any other kind of payment from O’Reilly Media, the publisher of the Head First books; I just think they are geniuses at making complex subjects much easier to understand than they otherwise would be – and I'm just an incorrigible evangelist for things that I like.